Why some families are returning adopted kids in Tamil Nadu

As soon as they heard from the nursing home that their surrogate had delivered a healthy baby, the adoptive parents (name withheld) informed the adoption agency of their decision to return the 8and 10-year-old siblings they had adopted a few months earlier. The children, who are now back in the adoption home, will be counselled for foster care or placement in a govt home where they may grow up as orphans.

Since 2020, about 12 parents in Tamil Nadu have returned children – less than 10 years old – who they legally adopted through various govt-certified agencies for different reasons. Four parents quoted “adjustment issues” as a reason for returning children. While one parent thought the toddler did not make enough eye contact during conversation another felt the child had anger issues. Some parents quoted marital or financial problems within the family, and others cited the child’s poor health. In one case it was the death of a parent. Officials confirmed that while three of them have been re-adopted, one is in foster care and the remaining still in govt homes.

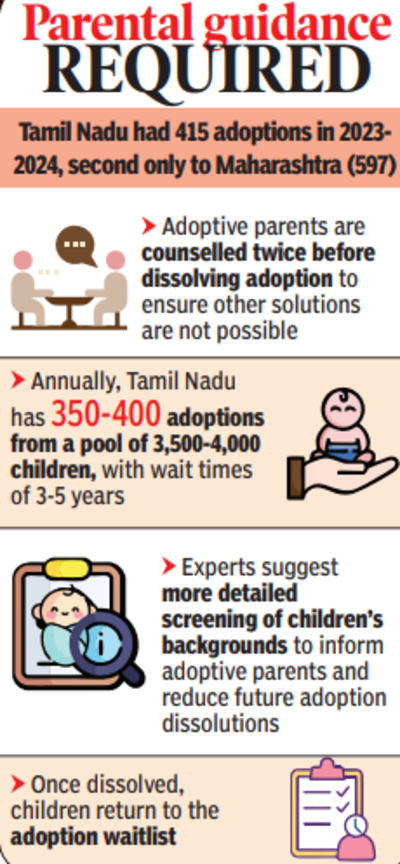

The social welfare department has recorded three dissolutions of adoption in 2020, four in 2021 and five in 2023. Protocols, however, are now being implemented to ensure they don’t happen again. “We counsel parents at least twice to see if we can help them retain the child. In some cases, we know parents may not have a choice. The adoption process is then dissolved to declare the adoption void,” says social welfare secretary Jayashree Muralidharan.

An authorised agency applies for dissolution to the district magistrate through the district child protection unit. Once the process is completed, the child is back on the list of those “legally free” for adoption. “Considering the long wait list, most children get another chance quickly,” says Muralidharan. “In general, most adoptions are successful. Dissolutions, however, have become unavoidable due to various reasons in some cases.”

Psychiatrists say parents who surrender adopted children cannot be villainised as they are seeing a rise in “adaptive challenges” for different reasons. First, as adopted children identified with early stressful childhood, many parents seek consultations for “behaviour issues” after complaints from siblings, neighbours and schools. “It’s tough on the child as well as the parent. Until some years ago, most adoptions happened within the family. A couple who do not have children will adopt their nephews or nieces, or from families known to them. The joint family system monitored the upbringing of the adopted child,” says child psychiatrist Dr V Jayanthini.

Today, information about biological parents is unknown in most cases, she says. “Mothers may not have had a happy pregnancy period. They may have neglected their diet and medical care, resulting in little bonding between the mother and the child after birth. All this can be stressful for the child. When they come to new homes the process of adapting themselves may add to this stress. While in many cases they tend to settle in with love and care, some children and parents just don’t get along.”

In such cases, children show pat terns of uncooperative and defiant behaviour (disruptive disorder), or they are always angry, irritable, argumentative or defiant (oppositional defiant disorder) or may express disregard for others (conduct disorders). In some cases, children may be diagnosed with neurodevelopment disorders such as autism. “I have seen such children in my clinics. They show less interest in education, pick up habits such as use of tobacco and alcohol in early teens. Some are at risk of self-harm too,” she says.

Genetics also plays a role. Studies have shown adoptees have a small but known risk for depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders, says psychiatrist Dr R Thara, vice-chairman of Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF). “It is not easy for parents to return the child too. We have seen cases where they do after making several attempts to build the family,” she says.

The social welfare department says it ensures all adoptive parents return the child without legal battles. “Our focus is on the child. The child should not feel unwanted or grow up in a place where he or she is not loved enough,” says Muralidharan.

Every year, about 400 children are adopted from nearly 4,000 waiting at homes authorised by Child Adoption Resource Authority (Cara) in Tamil Nadu. “The average waiting time for parents is three to five years,” says a caretaker at an adoption home. Every resident Indian prospective adoptive parent (PAP), who intends to adopt a child must register online in the Child Adoption Resource Information and Guidance System by applying in a prescribed format with relevant documents. “It is an intensive process. There is a home study report to evaluate parents,” says a govt social worker.

The physical and mental health conditions of the parents are evaluated as a part of the pre-adoption checklist. The govt also ensures adoptive parents are financially capable and have not been convicted in criminal cases. “There are stringent age regulations,” says the social worker. While couples must be married at least for two years, single men are allowed to adopt only boys. The age of the child allotted to a parent depends on the composite age of the parent. For instance, to adopt a child less than two years of age, the composite age of the parent must be 85 years and for children between two and four composite ages of parents must be 90 years.

Parents also get to see three children before they make a choice. “They may reject children who are unhealthy or disabled. Sometimes parents feel the child does not resemble them. If they don’t choose to be shown three options, they may go behind in the waiting list,” says a social welfare official.

Experts feel the state must consider introducing changes to bring down cases of dissolution. For instance, Dr Thara says it is important to screen children before giving them up for adoption. “Screening should include a detailed history such as heart disease, epilepsy and diabetes in the family so that they can be detected early and treated. A proper history of mental health conditions such as alcoholism, personality issues, and schizophrenia in the family is equally critical for the new families to be vigilant about symptoms. Disparity in educational and socio-economic status can also make the child uneasy and maladjusted,” she says. This may be difficult to do as the state may often have very little family history about abandoned or surrendered children. “So, those sent for read option must have details of the problems faced by the first adoptive parents. This is to ensure children do go through trauma again and parents know what they are going to face,” says Dr Thara.