Adoption: One man's quest to find his identity

Adoption: One man's quest to find his identity

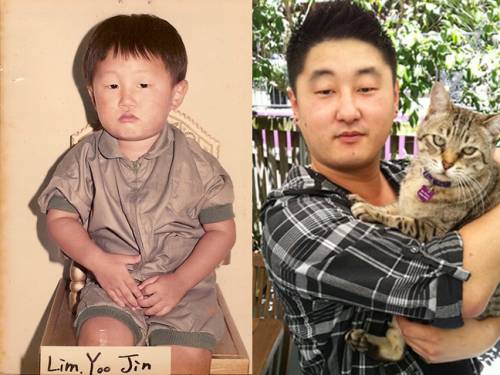

Tim Fredericks was born in South Korea, and adopted by an Australian family.

Tim Fredericks was adopted from South Korea as a baby. While he has had a loving and supportive upbringing, a lingering feeling of loneliness drove him to seek out his birth mother.

As a child, Tim Fredericks felt like every other kid – he went to school, played sport and hung out with friends and family.

“I felt normal like everybody else,” says Mr Fredericks, now 29 and a graphic designer.

“But when I tell people I’m adopted, they ask me a million questions and that makes me feel like I’m not normal.”

“I think the worst thing you can say to someone who is adopted is ‘sorry’. I know some people don’t mean any harm but I don’t feel like there is anything wrong with being adopted.”

Mr Fredericks was adopted from South Korea when he was three years old, and grew up in an ethnically mixed area on Sydney’s north shore.

Adopted into an Australian family of five that included an Australian adopted brother and Korean adopted sister, Mr Fredericks says he grew up in a loving and supportive family.

Yet, Mr Fredericks always felt lonely.

"I felt like I was born alone,” he says.

“That loneliness lingers on throughout life. It’s a little bit like identity crisis, not knowing your roots.”

“You only know what you look like in your own reflection but you don’t know the roots to your reflection.”

Mr Fredericks said he had used this as a source of strength in his life.

“I didn’t really struggle with loneliness. I just used that as a strength to build myself. I make my own energy,” he said.

Having grown up in a multicultural neighbourhood with Korean friends, Mr Fredericks said he always felt proud to be Korean Australian.

“I like to say I’m Korean and I’m proud. I have Korean blood. I’m proud of it even though I don’t know much about the culture. I think it’s because of how I look,” he laughed.

“I see myself in the mirror everyday so I might as well embrace it.”

Mr Fredericks was 25 before he became interested in finding his birth family.

His only lead was a document provided at the time of his adoption. It revealed his single mother was forced to relinquish him to avoid the social stigma of being unwed, and it was hoped adoption would provide him a better future. The document also said his biological father was a married senior manager at a toy factory and his mother a young employee.

“I have some kind of resentment towards my dad cause of what he did to mum but I don’t even know him which is unusual,” he says.

“My fantasy dream is that if I become rich, I’d go back and save her, buy her a house and make her happy.”

“It’s kind of lame and I don’t know why I feel this way. It’s hard to say goodbye to someone and she wouldn’t have wanted to let me go. It’s not her fault. She just wanted what was best for me.”

Mr Fredericks has tried to locate his mother four years’ ago. However, his search was cut short when the NSW Department of Community Services (DoCS) who manages inter-country adoption processes implied she had moved on and started a new family.

“I’m not prepared to not give it another go just based on those words,” he said.

“It may sound like bullshit but it’s just this inner feeling I get, that she is somewhere out there, trying to find me.”

“What if DoCS was wrong and she goes to church praying to be reunified? That would be such a shame. I’m doing this for her as well.”

Mr Fredericks adds that he would be happy to just visit the orphanage from which he was adopted, as it would help him piece together his past.

“I want to retrace where I came from. I want to see the kids in the orphanage now. I don’t have my birth parents so it’s the only roots I have left,” he said.

Asked about recent changes to the intercountry adoption program in South Korea, Mr Fredericks says he's concerned about whether the government was acting in the best interests of children.

“I think it’s a sad thing the South Korean government is reducing the number of inter-country adoptions,” he said.

“I know culturally Koreans have too much pride and they hide the fact that their kids are adopted.”

“It’s a shame that they are not as open as they should be.”