#SAVETHECHILDREN: HOW A FRINGE CONSPIRACY THEORY FUELED A MASSIVE CHILD ABUSE PANIC

Overview

A conspiratorial protest movement known as #SaveTheChildren swept across the United States, Canada, the UK, and Europe in the summer and early autumn of 2020, inspiring hundreds of in-person marches and demonstrations. The stated goal of the #SaveTheChildren campaign was to raise awareness around the horrors of “child sex trafficking,” a commonly misrepresented (although very real) problem in the United States and globally. However, much media coverage of this new movement initially failed to recognize that #SaveTheChildren was inspired by outlandish and debunked claims popularized by the online QAnon conspiracy movement; chiefly, the false notion that a “cabal” of politicians and celebrities participate in the satanic, ritual sexual abuse of children worldwide. By using social media to amplify misleading statistics and other misinformation, the #SaveTheChildren conspiracy movement contributed to an explosion of fear and anger surrounding child sex trafficking in the United States, and the proliferation of radical, conspiratorial beliefs that had previously been relegated to a relatively small, online community of conspiracy theorists.

Background

Sex trafficking – defined under U.S. law as “trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion” – is a real, troubling but commonly misunderstood problem. While the QAnon community’s understanding of the term “child sex trafficking” evokes the misleading image of children being kidnapped by strangers and then transported across statelines or international borders to be sold for sex, most real cases of sex trafficking of minors involve teenagers who are pushed to commercial sex work due to extreme poverty, abuse, or other devastating circumstances.1 In its 2020 “Trafficking in Persons

,” the U.S. Department of Justice describes certain minors in these circumstances as being particularly “vulnerable” to trafficking. These minors include “children in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, including foster care,” “runaway and homeless youth” and “unaccompanied foreign national children without lawful immigration status,” according to the

.2

In 2020, U.S. federal prosecutors identified 1,499 victims across all federal human trafficking prosecutions (including both sex trafficking and labor trafficking). Fifty-three percent of those victims – roughly 800 people – were children under 18, according to the "2020 Federal Human Trafficking Report."3 On average in the U.S. between 2010 and 2019, fewer than 350 people under the age of 21 were reported as abducted by a stranger (which is about 0.1 percent of total reported cases of missing children).4

However, followers of the QAnon conspiracy movement have come to believe child sex trafficking is a rampant problem. They falsely claim that 300,000 children are kidnapped and forced into sex work every year.5 This figure has been widely debunked. It is a misrepresentation of a nebulous estimation from a 2001 report of the number of children considered to be “at risk for commercial sexual exploitation,” published by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, based on data from the 1990s.6

Federal statistics show that child sex trafficking does not occur on the scale suggested by QAnon and #SaveTheChildren adherents. However, experts in the field widely agree that the known number of victims of sex trafficking (and human trafficking in general) is likely an underestimation, given the social stigma and barriers associated with reporting crimes of a violent and/or sexual nature; the same is true of victims of sexual assault, domestic violence, and other such crimes.7 As a result, the actual number of victims of child sex trafficking is very difficult to accurately estimate.

This creates a data void, which followers of QAnon and other conspiracy groups exploit to sow widespread anxiety about the prevalence of the problem by spreading misinformation and misleading statistics.

QAnon Origins and Folklore

The fringe conspiracy movement known as QAnon first emerged in October 2017, when an anonymous 4chan user (who would later become known as “Q”) claimed to be privy to top-secret government intel suggesting that Hillary Clinton was wanted by the federal government, and soon to be arrested. This was not true.

In subsequent posts made over the next several weeks, the anonymous “Q,” posted regular messages claiming many people in the government worship Satan, laying the foundation for the conspiracy movement. Q claimed, among other things, that then-President Donald Trump was waging a secret war against a vast satanic child sex-trafficking operation run by and catering to politicians, Hollywood celebrities, billionaires, and other political and cultural elites.8 None of these claims are true.

Over the next three years, a relatively small, committed group of internet users came to believe that Q was, in fact, a government insider or group of insiders, leaking top-secret government information to the public. They helped expand the conspiratorial belief system by “interpreting” Q’s cryptic, sometimes nonsensical messages within the context of their own preconceived conspiratorial beliefs.9 There are not many official estimates as to the size of the online community surrounding QAnon at this time, and even now, belief in QAnon remains difficult to measure.10 But a 2020 internal investigation by Facebook revealed that the top 10 QAnon groups on the

contained more than 1 million users, according to reporting by NBC.11

QAnon has been described by journalists and researchers as an “umbrella”12 or a “big tent”13 conspiracy theory because many of the tenets of the QAnon belief system were absorbed from preceding or tangentially related conspiracy theories. For example, QAnon adherents falsely believe that adrenochrome – a real chemical substance found in the human body – is extracted from the blood of abused children by non-existent satanic elites.14 These beliefs are reminiscent of theories concerning the “Illuminati,” the “New World Order,” and other, more nebulous anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic fears – all of which date back to at least the 18th century.15 The 2016 Pizzagate theory, which falsely claimed that then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton was operating a child prostitution ring out of a Washington, DC, pizza restaurant,16 is often considered the most direct precursor to QAnon.

Many scholars and journaliststs have also pointed out that widespread misbeliefs about the prevalence of pedophilia and child abuse pre-date the QAnon conspiracy movement, most notably tracing back to the Satanic Panic phenomenon of the 1980s and '90s.17

Since 2017, QAnon followers have often interpreted real-life news events concerning prominent allegations of sexual violence as fodder for new, unfounded conspiracy claims, or “evidence” of their previously-held beliefs.

For example, as the 2017 #MeToo Movement unfolded, many QAnon followers saw the allegations brought against prominent Hollywood studio executives, such as film producer Harvey Weinstein, as reason to believe that Hollywood and the entertainment industry writ large are hotbeds for sexual violence against children.

Similarly, in 2019, QAnon followers believed that the arrest for soliciting prostitution from a minor, and eventual suicide of billionaire Jeffrey Epstein as he awaited trial was “proof” that many (if not all) members of the global political elite regularly abuse and traffic children for sex. From 2017 to 2020, Q mentioned Weinstein by name twice in his messages, known as “drops.” Epstein, on the other hand, was explicitly mentioned more than 30 times.18 To date, both men remain prominent villains in QAnon folklore.

The identity of the person claiming to be “Q” remains unconfirmed (despite much speculation by journalists and others), but the community of Q supporters is led by a network of prominent social media

, many of whom command a large online following and regularly produce podcasts, video series, and other digital content dedicated to decoding Q drops. These influencers have popularized many coded slogans, catch phrases and other obscure calling cards within the larger community of believers, which a layperson might not recognize as related to the movement. For example, in QAnon phraseology, satanic elites who traffic and abuse children are referred to as “the cabal,” and their prophesied demise is known as “the storm.”19 One of the most common calling cards used by QAnon followers, often as a hashtag, is “WW1WGA,” short for “Where we go one, we go all.”

Beginning in 2018, QAnon followers occasionally used the phrase “save the children” or the hashtag #SaveTheChildren on social media when making vague references to “The Storm” or other Q-related theories. These posts rarely garnered much attention within the QAnon community, much less the mainstream discourse online.

Here are a few examples from Twitter:

Figure 1. A tweet by an unverified Twitter user using #SaveTheChildren in 2018, alongside the #PIZZAGATE hashtag and a reference to “The Storm,” a QAnon theory. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/LE9S-GVNGb. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 2. A tweet employing #SaveTheChildren in a reference to QAnon in 2019. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/L59L-PU2D. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 3. A tweet related to Jeffrey Epstein from 2019, containing the phrase “save the children.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZGB2-A39P. Credit: TaSC.

However, until 2020, the slogan and corresponding hashtag had never been widely used by the most influential members of the QAnon community. Indeed, #SavetheChildren was not widely associated with the QAnon community until 2020, when the phrase was catapulted into the public discourse by a global protest movement inspired by QAnon folklore.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

The popularization of the phrase “save the children” in relation to conspiracy theories about child sex trafficking began with Scotty “the Kid” Rojas,20 a Native American rap artist, model, and cryptocurrency enthusiast from Los Angeles, during the summer of 2020.

Figure 4. A screenshot from a YouTube music video for Rojas’s rap song, “Spitta,” which the video title describes as a “Bitcoin Anthem.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W2YP-4VYY. Credit: TaSC.

The primary tool that Rojas used to seed and propagate the #SaveTheChildren campaign was Instagram. However, research for this case study, which was conducted from November 2021 to February 2022, found that only a few, incomplete digital archives remained of Rojas’s

posts from that period.21

A September 2020 episode of the QAnon Anonymous podcast (QAA), an investigative QAnon

show, includes audio recordings from several of Rojas’s Instagram video posts, live streams, and stories about #SavetheChildren protests, as well as descriptions of several of his image posts from the summer of 2020.22

According to QAA, Rojas first showed interest in QAnon via his Instagram account on June 9, 2020, when he posted the following caption, “When someone calls you a conspiracy theorist, what they are really saying is they’re too lazy to do their own research, and we should just trust the government and the media to tell the truth;” along with the hashtag #Q.23

Prior to this post, the QAA hosts say that Rojas’s Instagram grid was mostly populated by stylized modeling shots, apolitical

, and clips from his music videos. Furthermore, Rojas’s public persona at the time (based on his social media feeds and rap lyrics) was that of a fairly apolitical, new-age musical artist who expressed little interest in conspiracy theories (outside of a few YouTube videos about supposed UFO sightings24 ).

But after his initial #Q post, according to QAA, “Scotty’s feed transformed profoundly in the span of a few months” to include many more references to child sex trafficking and other QAnon-related issues.25

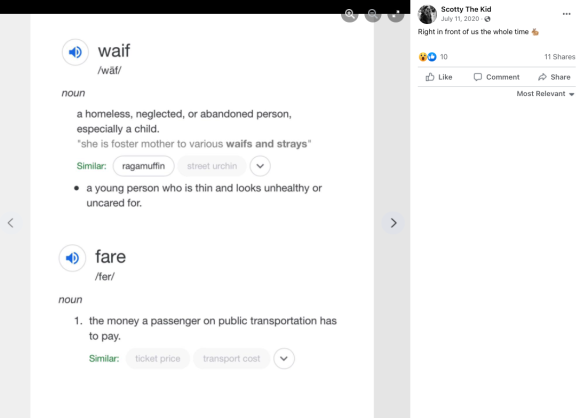

This change is also evident on Rojas’s Facebook profile which, as of November 2021, still featured posts from the summer of 2020.26 On July 11, 2020, for example, Rojas posted a reference to the Wayfair conspiracy27 – a QAnon-adjacent theory that suggested the online furniture retailer Wayfair was facilitating the sale of human children through cabinets.28

Figure 5. A meme related to the Wayfair conspiracy theory, posted by Scotty “The Kid” Rojas, on Facebook on July 11, 2020. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Z6E7-HRYT. Credit: TaSC.

These social media posts suggest that Rojas moved to begin a conspiratorial protest movement against child sex trafficking within weeks of showing public interest in QAnon for the first time.29

The timing of the campaign was also likely influenced, at least in part, by the substantial growth and public attention surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement that erupted after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. In an Aug. 17 interview with Sam Tripoli, host of the conspiratorial comedy podcast, Tin Foil Hat, Rojas said he suspected the anti-racism uprising was a “distraction” orchestrated by powerful people to obscure the more legitimate problem of child abuse and trafficking.30

“When BLM started happening, and I just saw just so much going on and some people being confused and being manipulated...So many things didn’t feel right about it with me,” Rojas told Tripoli. “And as I just dug more and more...I’m like, dude, this [child sex trafficking] is actually what’s happening here. This is the problem."31

The #SaveTheChildren campaign officially began when Rojas announced his plans to host an in-person march “to save the children” on July 22, 2020, via his Instagram story.

“Next Friday, I’m going on a march to save the children. I'm heading it up, and I would love for you guys to join me in Hollywood. Peep my next story post to see all the details,” Rojas said in the video, the audio from which can be heard in the QAA podcast.32

In the same interview with Tripoli, Rojas explained that he decided to hold the demonstration in Hollywood because – despite having grown up in Los Angeles – he believes the entertainment industry to be a hotbed for satanism, child sex trafficking, and other abuses.33 This is also a commonly-shared belief among QAnon followers34 and other conspiracy groups.35

In a blog post published on Aug. 28, 2020, Rojas elaborated:

Most of my life I’ve been a Musician, DJ, Model, Actor, and Entrepreneur…as I worked to keep my status in Hollywood, and then it became worse, as I began to realize just how deep the rabbit hole went. What I thought was just dark clothing, and demonic emblems, worn for pop culture value, and to “look cool”, actually turned out to be the symbolism of a real force, controlling and running parts of the entertainment industry; and more. Obviously, had I known that children were involved, I never would have affiliated myself with that crowd, or anything remotely close to that nature.

Also on July 22, the same day that Rojas announced his march “to save the children,” a website called Real Deal Media posted on Instagram that it would be organizing a “Child Lives Matter” march in Hollywood the same day as Rojas’s event.36

The outlet’s involvement with #SaveTheChildren was first reported in August 2020, by EJ Dickson at Rolling Stone magazine, who called the website “conspiracy theory-promoting.”37 Real Deal Media is owned and run by Dean Ryan, whose LinkedIn profile identifies him as a former InfoWars producer on “The Alex Jones Show.”38 At the time of publishing, Real Deal Media has some 1,300 followers on Instagram39 (compared to Rojas’s 36,00040 ).

Real Deal Media did not mention Rojas in its initial Instagram post promoting the “Child Lives Matter” march or any subsequent such posts, but both Real Deal Media and Rojas used similar versions of the same digital promotional poster to garner attention for the event. The first version of the image posted by Real Deal Media on July 22, 2020, had the organization’s own Instagram handle and web address displayed in the bottom right hand corner of the image, and featured the phrase “CHILD LIVES MATTER” in a red stripe. This post about the march earned 34 likes.41

Figure 6. A digital poster promoting the “Child Lives Matter” March in Los Angeles on July 31, 2020, posted by Real Deal Media on Instagram. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3XB2-BSEG. Credit: TaSC.

Rojas’s version, which he posted on Facebook that same day, appears to have the Real Deal Media branding obscured, and replaced with the acronym, “WWG1WGA.” This version also has replaced the “CHILD LIVES MATTER” phrase with “#BABIESLIVESMATTER.” Rojas’s version of the poster was shared 97 times.42

Figure 7. A slightly altered version of the same digital poster, posted on Facebook by Scotty “The Kid” Rojas. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/6N84-8Z6G. Credit: TaSC.

Both versions of the poster featured the hashtag #savethechildren and QAnon iconography, including a pizza slice (which some QAnon followers believe to be a coded symbol for child exploitation).

It remains unclear whether Rojas and Real Deal Media coordinated to organize or promote the first #SaveTheChildren march on Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street on July 31, 2020. Both Dean Ryan of Real Deal Media43 and Rojas later took credit for the event.44

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

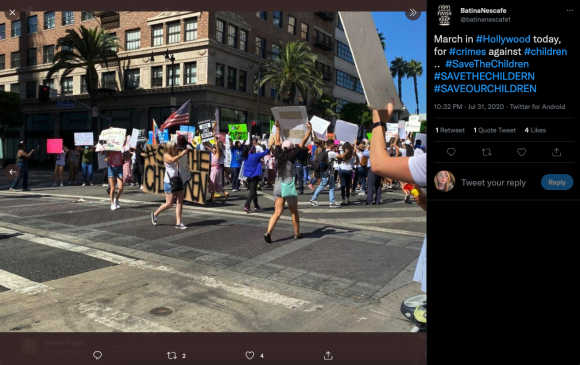

This first “Save The Children”/”Child Lives Matter” protest took place in Hollywood on July 31, 2020.

Photos and videos posted to social media during the event show a few dozen protesters holding signs containing numerous QAnon and Pizzagate references, including crossed out pizza slices and mentions of the “cabal.”

Figure 8. A Twitter thread posted by QAnon Anonymous podcast host Travis View, featuring multiple photos taken during the July 31 Save The Children March in Hollywood, CA. The first image shows a #SaveTheChildren protestor holding a sign with multiple references to QAnon folklore, including “adrenochrome” and an image of a pizza slice. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/G9BF-EJ4U. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 9. A tweet using the #SAVETHECHILDREN hashtag alongside a photo taken during the July 31 Save The Children March in Hollywood, CA. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8FMP-LVJD. Credit: TaSC.

During the demonstration, protestors marched down Hollywood Boulevard, through the “Walk of Fame.”45 In an effort to garner press attention and trade up the chain, the protestors gathered in front of the CNN office building, chanting “Where we go one, we go all.”46 The march eventually dispersed in front of Hollywood High School.47

Figure 10. An Instagram video taken during the July 31 Save The Children March in Hollywood, CA, showing a protestor holding a sign that reads “Pizzagate is real.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/F3LM-TPUV. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 11. A Twitter thread of several images taken during the July 31 Save The Children March in Hollywood, CA. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/84PL-RHGS. Credit: TaSC.

Rojas attended the event wearing a Guy Fawkes mask and a T-shirt with a large Q printed on it,48 and was photographed holding a sign that read: “F*CK THE NWO. F*CK VACCINATIONS. EXECUTE ALL PEDOPHILES!”49

Figure 12. An Instagram post showing Scotty “The Kid” Rojas at the Save The Children March in Hollywood on July 31, 2020. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2Z6B-RUQ4. Credit: TaSC.

In the days that followed, photos and video from the protest circulated on social media, often accompanied by the hashtag, #SaveTheChildren.50 On Twitter, the hashtag was used more than 2,600 times between July 31 and Aug. 5, 2020. These tweets earned a total of more than 66,000 retweets and over 82,000 likes.51

Other, associated hashtags from that same time period include #savethechildrenworldwide, #endhumantrafficking, #WWG1WGA, and #billclintonisapedo.

Figure 13. Word cloud containing the words most-often used within the roughly 2,600 tweets posted between July 31 and Aug. 5, 2020 that also contained #savethechildren. Generated via WeVerify, https://mediamanipulation.org/sites/default/files/media-files/stc_figur…. Credit: TaSC.

On Aug. 5, 2020, Rojas announced on Instagram that he would be organizing a second protest event, according to QAA. These demonstrations, he said, would take place across “one hundred cities” roughly two weeks later, on Aug. 22, 2020.52 Rojas dubbed the event the “100 City March.”

In order to achieve his goal of bringing 100 American cities into the anti-child sex trafficking fold, Rojas used Instagram to encourage his followers to personally head up a march in their own hometowns. “If you want to be a part of saving the children, step up, because right now is that time,” he said in an Instagram video.53

In the Tin Foil Hat interview, Rojas explained his process for recruiting participants in more and more cities:

I figured, ‘Hey, if I just use my Instagram as an actual platform for other people to communicate, I was like ‘Well, all I’d have to do is put a black box with the city name, and then the people – my followers – who live in that city can just comment there, can connect there, and DM each other and create their own movement,’ and it clicked…So that’s literally all I did.

Then, when someone would express interest in getting involved, Rojas told Tripoli that he would create a “syllabus” for them, complete with instructions on how to organize, host, and promote their very own local event as a part of the 100 City March.

“It’s a breakdown on how to do this correctly, how to do it legally, how to not interfere with businesses, with people’s lives, this is a peaceful thing,” said Rojas.

But not all #SaveTheChildren adherents took instruction from Rojas. In the weeks between the July 31 “Save The Children” protest and The 100 City March, at least nine other seemingly unaffiliated “anti-child sex trafficking” demonstrations were held in various cities across the United States, including Chicago,54 Savannah,55 and Spokane.56 This fact suggests that the Rojas campaign message had already carried far enough to inspire copycats.

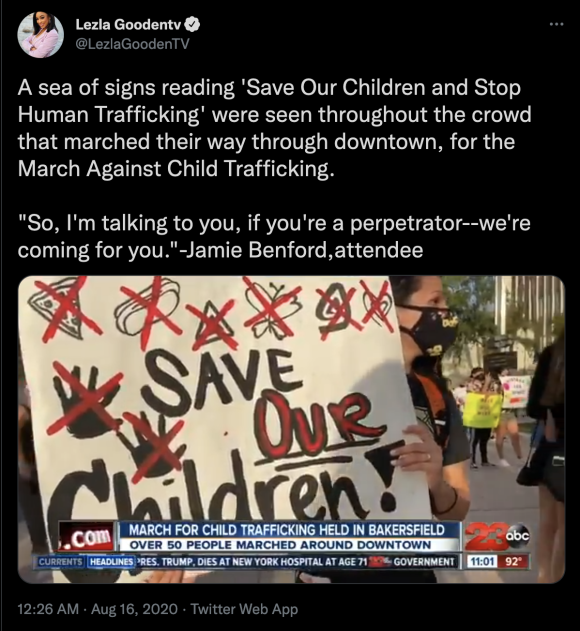

Figure 14. A Twitter video showing a “March Against Child Trafficking” on Aug. 16, posted by a reporter for ABC 23, which shows a protester holding a sign featuring QAnon iconography and the phrase “Save Our Children.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/MSA8-X6LY. Credit: TaSC.

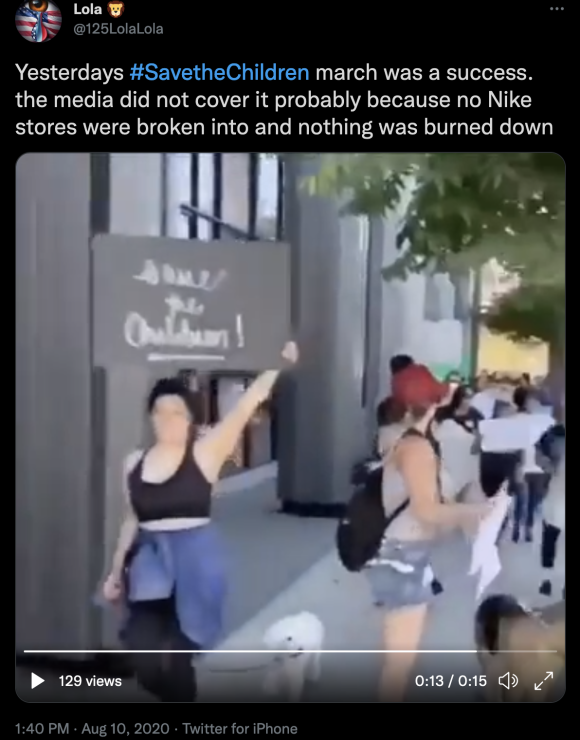

Figure 15. An tweet posted by an unverified user, describing an Aug. 10, 2020 #SaveTheChildren event as a “success.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/UJ8B-MHWG. Credit: TaSC.

This marked a turning point for the weeks-old campaign, because it indicated that #SaveTheChildren had – intentionally or otherwise – become decentralized. Anyone across the country (or the world) could participate in the campaign by using social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter to organize a local #SaveTheChildren event; with or without Rojas’s help.

“I am asking all my followers to retweet this with your state and which part of your state so we can find co ordinate [sic] a meeting place to set up the #SaveourChildren protest[.] I am South Arkansas. Other South Arkansas please reply to me,” wrote one unverified Twitter user on Aug. 18, in a typical call-out to fellow campaign participants.57

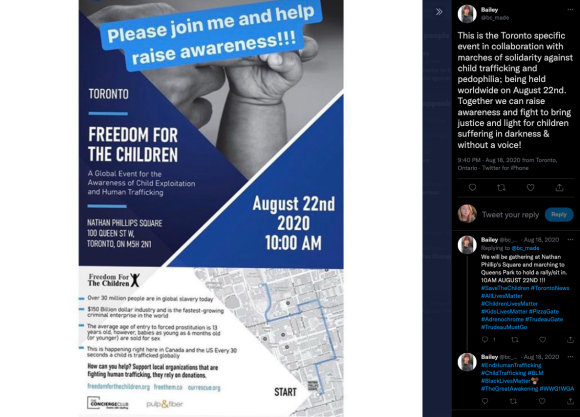

“Together we can raise awareness and fight to bring justice and light for children suffering in darkness & without a voice!” posted another Twitter user that day, alongside a digital flier for a local event in Toronto and the hashtags #Pizzagate and #WWG1WGA.58

“Let's stand together against pedophilia and human trafficking. Click the link to join my event. 🙏❤ #SaveOurChildren,” wrote a third Twitter user on Aug. 20, along with a link to a now-deleted Facebook event which presumably contained logistical details about this particular protest.59

Figure 16. A Twitter thread advertising a “Freedom for The Children” event on Aug. 22, in Toronto, posted by an unverified user. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/67VG-JUPH. Credit: TaSC.

Importantly, because these demonstrations were typically not advertised as QAnon-affiliated or conspiracy-inspired events (much like Rojas’s initial march), the campaign participants attracted a more mainstream audience of people genuinely concerned for the well-being of children. These people would otherwise not have been likely to publicly align themselves with an extremist conspiracy movement.60

It was at this point that the #SaveTheChildren campaign effectively became unmoored from its roots in the QAnon belief system. It branched off into a distinct – although still very intertwined – conspiracy movement dedicated to spreading misinformation about human trafficking.

As the movement grew, some participants even rejected any association with QAnon and its community. For example, one Instagram user posted on Aug. 22, “Human trafficking is the [sic] real[.] That’s why we need to stop associating it with the Q conspiracies.”61

Figure 17. A pro-#SaveTheChildren Instagram post calling for followers to “stop associating” the “movement” with QAnon. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/26CC-VHZN. Credit: TaSC.

Even Rojas, who had previously expressed strong support of QAnon, wrote explicitly on his website: “We are a grassroots organization, founded by We The People…we're NOT affiliated with Antifa, QAnon, or any corporate/political/religious agenda. Period.”62

This dilution of the QAnon narrative within #SaveTheChildren allowed the campaign to further trade up the chain; garnering local media exposure that treated the gatherings as positive local activism organized by concerned citizens, and lending legitimacy to the campaign’s conspiratorial narrative.63 New York Times Journalist Kevin Roose described this development as a “blurring of the lines” between “legitimate anti-trafficking activism and partisan conspiracy mongering.”64

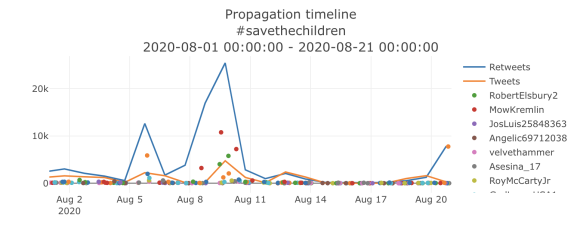

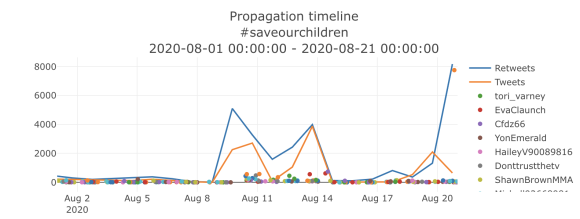

As Rojas’ 100 City March neared, and ancillary #SaveTheChildren protests continued to garner local press attention, the campaign’s affiliated hashtags began to skyrocket in popularity on nearly every major social media platform.

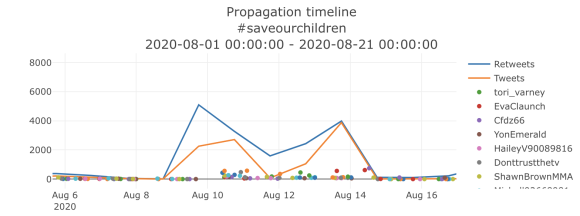

On Twitter, although #SaveTheChildren never made it to the “Trending Topics” list, more than 22,000 posts containing #SaveTheChildren were posted between Aug. 1 and Aug. 21, garnering more than 85,000 retweets.65 Similarly, #SaveOurChildren was tweeted more than 14,000 times in that same period, and retweeted more than 29,000 times.66

During the same time period, #WWG1WGA appeared in more than 14,000 tweets, which garnered just over 14,000 retweets.67 #BlackLivesMatter, meanwhile, was retweeted more than 139,000 times, according to Twitter analysis conducted via WeVerify.68

Figure 18. Use of “#SaveTheChildren” on Twitter, between Aug. 1 and Aug. 21, 2020. Generated via WeVerify, https://mediamanipulation.org/sites/default/files/media-files/%23saveth….

FIgure 19. Use of “#SaveOurChildren” on Twitter, between Aug. 1 and Aug. 21, 2020. Generated via WeVerify, https://mediamanipulation.org/sites/default/files/media-files/%23saveou….

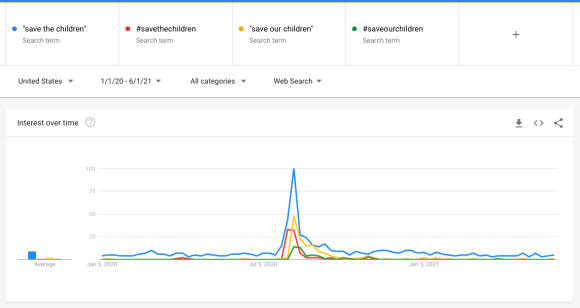

The number of

searches for “save the children” and similar phrases followed a similar pattern as the Twitter activity, spiking between Aug. 9 and 15, according to Google Trends.69

Figure 20. Google Trends results for “save the children,” “#savethechildren,” “save our children,” and “#saveourchildren,” between Jan. 1, 2020, and June 1, 2021, archived via perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4TBZ-L9JB.

The #SaveTheChildren hashtag became especially popular on Instagram, among prominent parenting, fitness, natural healing, and lifestyle influencers. It particularly attracted women influencers in these spaces, whose signature aesthetic inspired the colloquial term, “pastel QAnon.”70 Journalists and researchers occasionally use this term to describe QAnon-inspired rhetoric online that is packaged in the soft-hued color schemes, decorative fonts, or other feminine-coded aesthetics that have become commonly associated with these online communities.71

Figure 21. An Instagram post by Influencer Maddie Thompson (@madluvv21) using #SaveTheChildren on July 27, 2020. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/47WU-8PQE. Credit: TaSC.

In a 2021 analysis of the accounts that posted or interacted with hashtag #SaveTheChildren on Instagram, researchers at the University of Washington identified the campaign’s “primary contributors,” meaning those who posted the most often about the movement. They found that this group consisted of largely “conservative leaning, white, highly religious female-presenting accounts with a particular emphasis on motherhood.”72

Describing this development in Sept. 2020, Vox Senior Reporter Anna North wrote that #SaveTheChildren “may be feeding on the anxiety parents are experiencing in a time when families are stuck at home with many schools remote or operating on a hybrid model, leaving parents (disproportionately moms) to balance work, child care, and the ever-present risk of Covid-19.”73

Lifestyle and parenting influencer Rose Henges (@roseuncharted) posted an image featuring the #SaveTheChildren hashtag on Instagram on July 13, along with a caption containing incorrect statistics about human trafficking.74 According to BuzzFeed News Reporter Stephanie McNeal, Henges was one of the earliest influencers on the platform to embrace QAnon-adjacent rhetoric.75

Figure 22. An Instagram post by Influencer Rose Henges (@roseuncharted), using #savethechildren and saying, “HUMAN TRAFFICKING IS THE REAL PANDEMIC.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/9BSZ-XBCV. Credit: TaSC.

But the campaign’s influence was not limited to social media. Several campaign participants founded anti-child sex trafficking advocacy groups between May and September 2020, bearing names such as Freedom For the Children,76 Where’s Our Children,77 Save Our Children UK,78 and a group called Child Lives Matter.79 Many of these groups went on to promote the 100 City March – although not always using Rojas’s branding80 – as well as other in-person protests to raise awareness around child sex trafficking.81 Sometimes these groups raised funds or sold merchandise under the auspices of offsetting operational costs.82 Rojas launched his own advocacy organization, Stop Kidding, on Aug. 23, 2020.83

This newfound vigor for the #SaveTheChildren campaign culminated on Aug. 22, 2020, when The 100 City March took place. According to a list of participating cities circulated by Rojas,84 upwards of 250

#SaveTheChildren protests were held across the US,85 Canada,86 the UK,87 and parts of Europe88 on Aug. 22, 2020.

The TaSC team has not been able to locate official estimates of the crowd sizes at these disparate protests. However, photos and videos posted to social media on Aug. 22 show that some local gatherings attracted only a handful of people,89 while others drew much larger crowds.90 Jesselyn Cook, a senior reporter for HuffPo, tweeted that there were “easily hundreds of people” at a Los Angeles leg of the march.91

Figure 23. An Instagram post showing #SaveTheChildren protestors in Tallahassee, Florida on Aug. 22, 2020. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/PXX4-7RFV. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 24. An Instagram post showing #SaveTheChildren protestors in Dallas, Texas, on Aug. 22, 2020. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/RRW4-Y7LG. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 25. Instagram post showing #SaveTheChildren protestors in London, England. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7KXU-EZJE. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 26. Instagram post showing #SaveTheChildren protestors in Glasgow, Scotland. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/K2HY-QMGZ. Credit: TaSC.

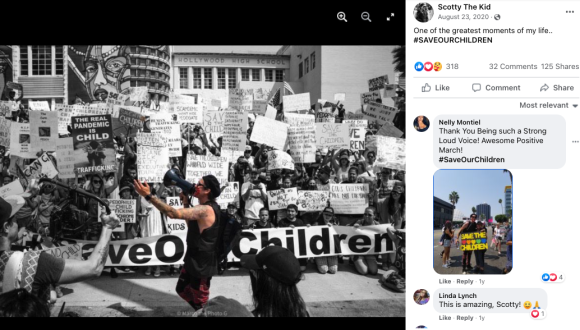

Rojas led the Hollywood leg of the march, and described the event on Facebook as “one of the greatest moments of my life.”92

Figure 27. Scotty “The Kid” Rojas posting on Facebook about the Los Angeles leg of the 100 City March, on Aug. 23, 2020. Along with a picture of himself speaking into a megaphone, Rojas posted the caption, “One of the greatest moments of my life.. #SAVEOURCHILDREN.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/FJ8H-4UVG. Credit: TaSC.

In contrast, a month prior, NBC Los Angeles reported that a Black Lives Matter protest hosted on the same street drew an estimated 20,000 people.93

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

Throughout Aug. 2020, as #SaveTheChildren rallies continued to crop up around the country and Rojas continued to promote the 100 City March, the #SaveTheChildren hashtag proliferated on social media. Many celebrities – including martial artist and actor Cung Lee94 and reality TV stars Jenelle Evans,95 Kelly Dodd,96 and Siggy Flicker97 – used it.

National Football League superstar Tim Tebow, who is well-known for his Baptist faith,98 used the hashtag to promote a new anti-sex trafficking “Rescue Team” within his eight-year-old, $8 billion philanthropic organization, the Tim Tebow Foundation. The Rescue Team’s website describes the project as “an army of people committed to engaging, inspiring, and equipping others in the fight against child sexual exploitation and human trafficking.” The foundation, which is a registered 501c3 non-profit organization, accepts donations from the public.99

Several politicians and political candidates also adopted the #SaveTheChildren slogan, and interacted with the campaign to varying degrees – and with seemingly various levels of understanding about its QAnon roots.

Georgia Rep. Buddy Carter, a Republican, attended a #SaveTheChildren rally in Savannah on Aug. 9. A spokeswoman for Carter later told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that the congressman had been invited to the event by a constituent, and that he “had no knowledge of any QAnon ties to the event.”100

Utah Attorney General Sean D. Reyes, also a Republican, used his office’s official Twitter account to promote a Salt Lake City “Freedom For The Children” gathering scheduled for the same day as the 100 City March.101 “Join us in raising awareness for human trafficking and child exploitation tomorrow at 9AM at Liberty Park in SLC,” the Aug. 21 post read. Hours after Reyes’s tweet was posted, local news station KUTV2News reported that the event had been postponed "due to questions about association with other human trafficking events being held the same day."102

Then-Republican congressional candidate Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia also employed the #SaveTheChildren hashtag a handful of times on Twitter, beginning in August, 2020.103 By this time, Greene had already become known as the “QAnon candidate”104 by political opponents and journalists. Throughout her winning 2020 congressional campaign, she publicly expressed support for QAnon in multiple Facebook videos105 and contributions to American Truth Seekers, a now-defunct outlet that NBC called a “conspiracy news website.”106

One of Greene’s first uses of the hashtag was in defense of Tim Tebow on Aug. 29, 2020, when his own use of the slogan garnered critical press coverage on Fox News.107

“The media is so obsessed with trying to attack Christian Conservatives that they can’t even comprehend that #SaveTheChildren is a fight every single one of us should be battling,” Greene wrote on Twitter. “I support @TimTebow And let’s #SaveTheChildren.”

Many of the #SaveTheChildren rallies – and particularly those held before the 100 City March on Aug. 22 – were covered uncritically by local television news stations and newspapers that failed (with some exceptions108 ) to recognize the movement’s roots in the QAnon belief system. These reports often employed the phrase “save the children” in the headlines,109 and featured quotes from local organizers and rally attendees.110 They typically did not mention Rojas’s role in kick-starting the movement, its relationship to the QAnon conspiracy community, or campaign participants’ misleading claims about child sex trafficking.

Meanwhile, within the more hardcore QAnon community, reactions to the #SaveTheChildren movement were mixed.

Despite the two movements sharing a goal of exposing the so-called “realities” of child sex trafficking, many dedicated QAnon followers did not see #SaveTheChildren as an extension of their own movement. As outlined in Stage 1 of this case, Rojas was not an established figure in the QAnon network when he launched the campaign, and although some QAnon believers embraced his message, others grew skeptical of his intentions.

Beginning in August, around the time of the 100 City March, some QAnon followers began to suggest that the #SaveTheChildren movement might be a coordinated conspiracy against QAnon, waged by members of the cabal to “co-opt” QAnon’s goals and values.111

“Of course save the children [sic] is comped,” wrote one anonymous 8kun user, posting to the “QResearch” board on Aug. 22. By “comped,” the user means “compromised,” assumedly by shadowy forces.

Another user agreed, commenting, “Classic attempt to coopt movement. FF incoming. Remain vigilant.”112

Here, “FF” stood for “false flag,” a term conspiracy theorists use to describe an attack carried out by a government or other powerful entity that implicates another entity as the perpetrator.113

The next day, a third user noted that #SaveTheChildren had to be some sort of cabal-related operation because (they argued) if it had been organized by other QAnon followers, they would have heard about it sooner.

“Told spouse anon today it was absurd that we would be having ‘nationwide’ rallies for ‘save the children,’" the person wrote. “I'm on here everyday and we've never once discussed organizing something like that.”114

STAGE 4:

efforts

Throughout the #SaveTheChildren campaign, social media platforms, non-profit organizations, and others made several attempts to prevent campaign operators from spreading misinformation about child sex trafficking online. Many of the mitigation efforts put in place in 2020 remained in effect 18 months later, when this case was published.

On Aug. 5, 2020, six days after Rojas’s first protest in Hollywood, Facebook made the first effort to mitigate #SaveTheChildren. The platform temporarily restricted the distribution of the #SaveTheChildren hashtag, describing the decision as a means of restricting the spread of content related to QAnon. This meant that “posts using the hashtag will have their visibility reduced in the News Feed and people clicking on the hashtag will not be able to see the aggregated results,” a Facebook spokesperson told CNN in a statement.115

The restriction was short-lived. By Aug. 12 a different Facebook spokesperson told Rolling Stone magazine that the hashtag had been “restored,” but provided no reason for the decision.116

Another early effort to push back against #SaveTheChildren came on Aug. 7, in the form of a civil society response from the well-known humanitarian organization Save The Children. The group – which has been providing education, food and health services to children worldwide for more than 100 years – published a press statement117 and corresponding tweet118 distancing itself from the

campaign using its name.

“Our name in hashtag form has been experiencing unusually high volumes and causing confusion among our supporters and the general public,” the statement read. “While people may choose to use our organization’s name as a hashtag to make their point on different issues, we are not affiliated or associated with any of these campaigns.”119

After the release of this statement, Rojas instructed campaign participants to use hashtag #SaveOurChildren, rather than #SaveTheChildren, according to QAA.120 Twitter data analyzed via WeVerify show that the use of “#saveourchildren” shot up in the days that following this announcement by Rojas.

Figure 28. Use of the #SaveOurChildren hashtag on Twitter, between Aug. 1 and Aug. 21. Generated via WeVerify, https://mediamanipulation.org/sites/default/files/media-files/%23saveou….

From then on, the two viral slogans were largely used interchangeably by campaign participants.121

Save The Children’s disavowal of #SaveTheChildren sparked a wave of

aimed at the campaign, chiefly from national news outlets with dedicated beat journalists familiar with online communities and digital conspiracy movements. At least two dozen stories published between early August and late October 2020 revealed the true nature of #SaveTheChildren as being inspired by conspiratorial beliefs popularized by QAnon.122

A few of the earliest critical articles include a Politifact explainer on how “QAnon, Pizzagate conspiracy theories co-opt #SaveTheChildren,”123 and a New York Times article outlining how and why “QAnon Followers Are Hijacking the #SaveTheChildren Movement.”124

These articles successfully identified the connection between #SaveTheChildren and QAnon. But many explainers published during this period nonetheless over-simplified the nature of that connection, suggesting that the two were not, in fact, distinct conspiracy movements.

Exceptions to this trend include Mel Magazine’s article on “How ‘Save The Children’ Became A Conspiracy Grift”125 and a piece in the Colorado Times Recorder called “Denver Anti-Child Sex Trafficking March Rooted in QAnon Conspiracy Theories.”126

In late Oct. 2020, more than 130 established non-profit organizations that advocate for victims of human trafficking – including Polaris and the Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking (CAST) – signed and published an open letter asking political “Candidates, the Media, Political Parties, and Policymakers” to “condemn QAnon” and other “conspiracy theories and

about sex trafficking aiming to sow fear and division in order to influence the upcoming election.”127

The letter did not explicitly mention the #SaveTheChildren campaign, but it avers that, “Anybody – political committee, candidate, or media outlet – who lends any credibility to QAnon conspiracies related to human trafficking actively harms the fight against human trafficking.”128

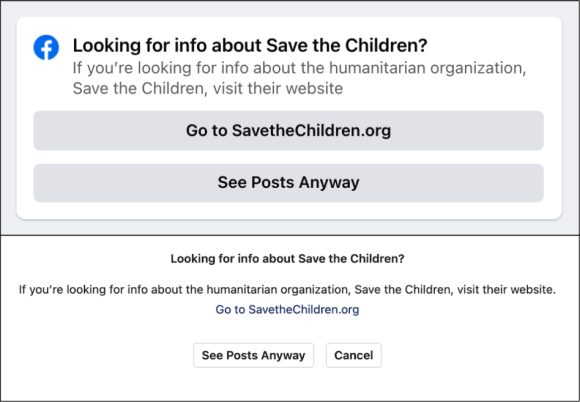

By early 2022, many of the Facebook event pages associated with the #SaveTheChildren movement had been removed. A February 2022 search for #SaveTheChildren on both Facebook and Instagram returned a content label redirecting the user to the official website of the philanthropic organization Save The Children.

However, on both Facebook and Instagram, users need only click a button reading “See posts anyway” to view all remaining posts featuring the hashtag.

Figure 29. Screenshots of the content labels that appear when one searches for “#savethechildren” on Instagram and Facebook. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/NXQ5-L8DL. Credit: TaSC.

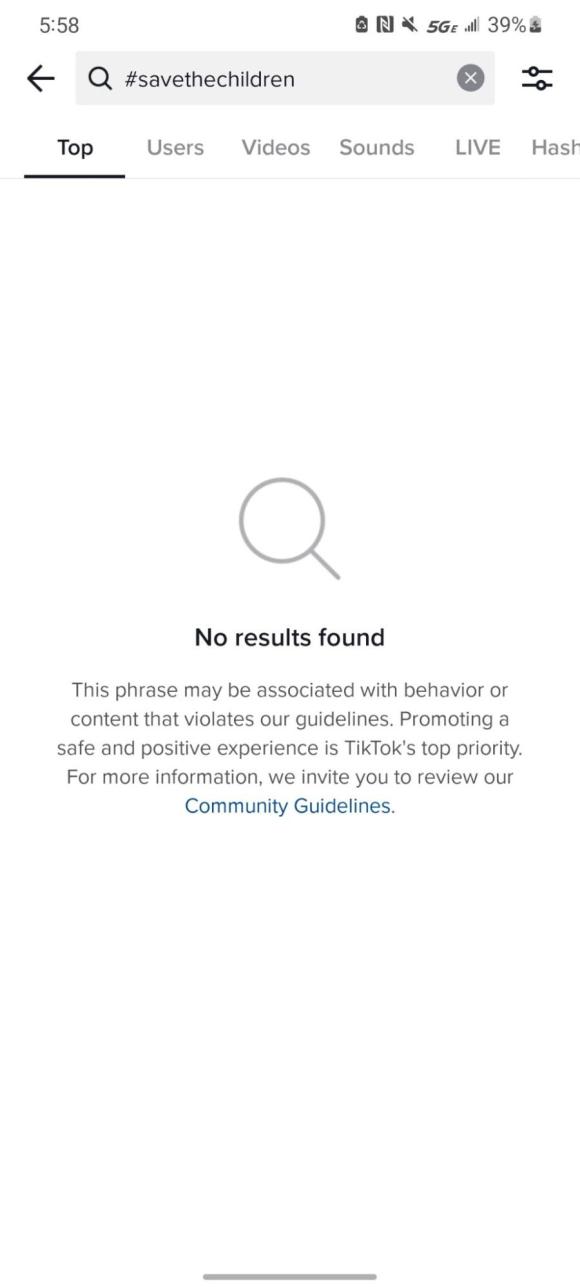

On

, a search for #savethechildren returns a warning that the phrase “may be associated with behavior or content that violates our guidelines” and offers no content featuring the hashtag.

Figure 30. A screenshot of the content warning that comes up when one searches for “#savethechildren” on TikTok. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/YZ4A-DH86. Credit: TaSC.

Despite all this mitigation, #SaveTheChildren protests – many unaffiliated with Rojas – continued to take place. Through September and into October 2020 cities such as Olympia, Washington, Phoenix, Arizona, and Wichita Falls, Texas, all saw anti-child trafficking marches.129

STAGE 5: Adjustments by campaign operators

Soon after its launch, #SaveTheChildren followers took on new targets, and new tactics.

In August 2020, American streaming giant Netflix announced on Twitter that it would soon be releasing a French film called Mignonnes (Cuties in English) in the United States. According to Vulture, the film – which follows a dance troupe made up of preteen girls – had received “relatively positive” reviews at the Sundance Film Festival, in part for its criticism of the harsh expectations placed upon young women by a patriarchal society.130

However, the film’s announcement was met with backlash on social media. Some users took issue with the movie’s promotional poster (not with the film itself, which had not yet been released). In it, the young dancers wear crop top uniforms and strike poses that some considered age-inappropriate.131

“Netflix WTF IS THIS,” one unverified Twitter user wrote in response to the Cuties poster on Aug. 19, 2020. “This [sic] is fucking disgusting. minors shouldn't be sexualized like this,” the user added in a second post.132

This user’s initial tweet received more than 30,000 retweets and 166,000 likes before being deleted.133 The success of this tweet was particularly striking, given the fact that digital archives show this user had less than 700 followers in April 2020, and their other posts did not typically earn more than a handful of likes.134

Figure 31. A viral tweet thread criticizing the film “Cuties.” Archived on Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20200823002727/https://twitter.com/littlewa…. Credit: TaSC.

Social media posts and critical press from this time show that #SaveTheChildren participants immediately saw Cuties as a flagrant example of the sexual exploitation of children they believed to be rampant in Hollywood and beyond.135

In a campaign adjustment, many participants called for their followers to cancel their Netflix subscriptions in protest of the film, under the hashtag #CancelNetflix.136

“Cuties is a pedophile’s dream,” wrote one Instagram user on Sep. 13, along with a picture of herself wearing a “Save Our Children” t-shirt. “There are a few things I’m really passionate about and when it comes to children- I won’t stay quiet. #cancelnetflix #saveourchildren.”137

Figure 32. An Instagram post from user @jazzzyyy13, featuring a picture of a woman wearing a “Save Our Children” T-shirt. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/RV5F-2UP2. Credit: TaSC.

The #SaveTheChildren-adjacent hashtag #CancelNetflix allowed the campaign to appeal to an even wider audience across various social media platforms, particularly among concerned parents who disapproved of the controversial film.138 #CancelNetflix became so widely used on Twitter, for example, that the hashtag reached the “Top Trending” topics list on Sep. 10, the day of the film’s release.139 And five days later, on Sept. 15, Variety reported that the campaign had successfully caused U.S. subscription cancellations to surge.140

The Cuties controversy and corresponding #CancelNetflix campaign effectively reinvigorated the #SaveTheChildren movement by attracting press attention from right-wing

.141 It also brought a handful of prominent politicians into the fold. Texas Senator Ted Cruz, for example, called the film “disgusting and wrong” and demanded a federal investigation as to “whether Netflix, its executives, or the filmmakers violated any federal laws against the production and distribution of child pornography.”142

In a tweet posted Sep. 11, 2020, former Democratic presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard declared the film would “help fuel the child sex trafficking trade.”143

Nevertheless, by early October 2020, #SaveTheChildren rallies began to dwindle. Scotty Rojas’s website shows that the last event he organized took place on Oct. 10.144 Rojas has since removed most of the posts related to #SaveTheChildren from his Instagram account, and has not promoted any other in-person events related to the campaign since.

But the categorically false claims about child sex trafficking born out of the #SaveTheChildren and QAnon movements have continued to thrive online. Their existence has severely muddied the waters in discourse about human trafficking.

Political science researchers Joseph Uscinski and Adam Enders found in October 2020 that most Americans seriously overestimate the prevalence of human trafficking nationally. Their study aimed to measure the popular impact of QAnon and related conspiracy theories by asking survey respondents whether “the number of children being trafficked in the US was above, about, or below 300,000 children.” This question was designed as a reference to the false but widely-shared statistic popularized by QAnon followers online.145

The researchers found that “50 percent of Americans think the real number of trafficked children is about 300,000 or higher. Thirty-four percent think it is ‘much higher.’”146

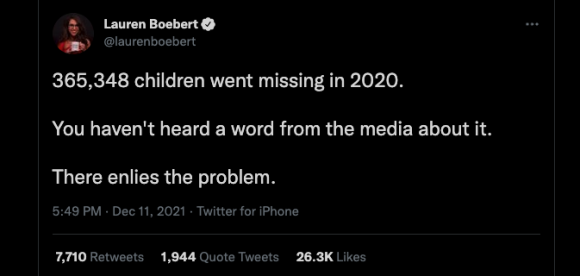

Those misinformed about the prevalence of child sex trafficking include powerful public figures, and even policymakers. For example, in Dec. 2021, Colorado Rep. Lauren Boebert, a Republican and known QAnon supporter,147 tweeted, “365,348 children went missing in 2020. You haven't heard a word from the media about it. There enlies [sic] the problem.”148

Figure 33. A tweet by Rep. Lauren Boebert about missing children, posted on Dec. 11, 2021. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/A3SQ-NZWH. Credit: TaSC.

Although the campaign waned in Oct. 2020, the inaccurate beliefs spread by #SaveTheChildren continue to inspire occasional, typically localized redeployments, in the form of in-person protests and fundraisers for dubious organizations that claim to be working to end human trafficking or providing aid to survivors.149

“All over the country, community volunteers promote awareness of child sex trafficking,” wrote journalist Kaitlyn Tiffany in a Dec. 2021 feature published in The Atlantic. In ithe article, she describes her experience at one such fundraising event. The “Festival of Hope” in Oakdale, California had a block party vibe, Tiffany writes, complete with food trucks and carnival rides.

Her story includes a laundry list of other nominally anti-trafficking fundraisers underway across the U.S: “In Colorado, at a Kentucky Derby party. In Arkansas, at an Easter bake sale. In Texas, at a ‘Big A$$ Crawfish Bash.’ In Idaho, at a Thanksgiving-morning ‘turkey run.’ In Utah, at an annual winter-holiday fair.”150

Today, the #SaveTheChildren campaign slogan continues to serve as popular merchandising fodder, emblazoned on T-shirts, sweaters, buttons, posters, and car decals sold on

Figure 34. An Etsy listing for a T-shirt featuring the phrase “Save the children,” sold for $18.95. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3E54-A9MN. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 35. An Amazon listing for a hoodie sweatshirt featuring the phrase “Save our Children,” sold for $27.82. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2HTV-LSBF. Credit: TaSC.

Figure 36. An Etsy listing for a vinyl decal sticker featuring the hashtag #savethechildren, sold for $4. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/YR35-YV8V. Credit: TaSC.

The ubiquitous, #SaveTheChildren hashtag and slogan has also been co-opted by several other protest movements since 2020, including by activists opposing COVID-19 interventions.153

Recently, at an anti-COVID-mandates protest in front of San Francisco City Hall on Feb. 8, 2022, at least one person held a “save the children” poster. When asked by a TaSC researcher how the sign related to COVID, the protestor replied, “Save the children from the vaccines.”

Figure 37. An anti-vaccine protestor in front of San Francisco City Hall on Feb. 8, 2022 holds a sign that reads, “SAVE THE CHILDREN.” Credit: TaSC.