De facto statelessness places adoption on the table for children of N.Korean women in China

| De facto statelessness places adoption on the table for children of N.Korean women in China |

| Proponents say adoption is one solution to complex legal and social issues, while critics say it bypasses resolving root causes and is not in the child’s best interests |

|

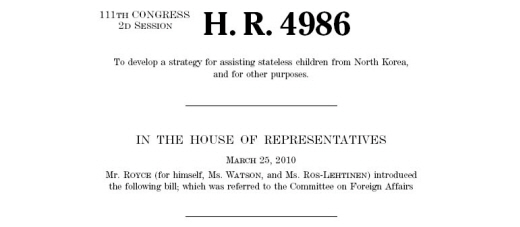

In an effort to address legal obstacles faced by children of North Korean mothers in China, the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a bill proposing a solution on March 25 of this year. The bill, H.R. 4986, is also known as the “North Korean Refugee Adoption Act of 2010.”

The bill’s purpose is “to develop a strategy for assisting stateless children from North Korea, and for other purposes.” The same bill, S.3156, was also introduced into the U.S. Senate two days prior.

The bill has been backed by Liberty in North Korea (LiNK), an NGO that works with North Korean defectors. LiNK worked with legislators during the drafting process. The NGO has also campaigned for the bill by screening a film at campuses, community centers, and churches across the United States, according to LiNK President Hannah Song.

H.R. 4986 proposes inter-country adoption as a solution to resolve issues surrounding children of North Korean women living in China and recommends that the U.S. Secretary of State “develop a comprehensive strategy for facilitating the adoption of North Korean children by United States citizens.”

Such documentation is a requirement of the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption, which sets out international principles that govern inter-country adoption. The Hague Convention, of which China is a signatory, “seeks to ensure that intercountry adoptions are made in the best interests of the child and with respect for his or her fundamental rights, and to prevent the abduction, the sale of, or traffic in children.”

“The tough challenge with North Korea and even with what we saw with Haiti, for example, was that documentation was destroyed,” said LiNK President Song. “And for North Korea, it just does not exist.”

De Jure vs. De Facto Statelessness

Children of North Korean mothers and Chinese fathers face a number of significant and diverse legal obstacles that ultimately lead to difficulties in securing citizenship in China.

Although they are legally entitled to Chinese citizenship, children face obstacles in obtaining hukou, a family registry certificate. Such a certificate is difficult to obtain under current practice. This is because although not required by law, the Chinese father must submit legal proof including testimonies from witnesses that his North Korean wife has been arrested and repatriated back to North Korea. This is a requirement because the mother may not be listed on the hukou due to her status as an illegal economic migrant, since China currently does not recognize North Korean border crossers as refugees. As a result, families are caught between having to leave children in de facto statelessness, as they cannot obtain hukou, or having to split up the family, both of which could become root causes for abandonment and eventual stateless orphan status.

“Many North Korean children of Chinese fathers and North Korean mothers live in legal limbo,” said Kay Seok of international NGO Human Rights Watch in her report, “Denied Status, Denied Education: Children of North Korean Women in China.”

“Children are nationals of North Korea, meaning entitled to South Korean citizenship at the same time, even if children already have dual nationality from China and North Korea,” said international human rights lawyer Kim Jong-chul. “Children are stateless not in the de jure sense, but in a de facto sense because their Chinese birth fathers do not register them under the family registration system, which prevents them from receiving educational and medical services.”

Inter-country Adoption

Inter-country adoption remains a complex issue in Northeast Asia. An estimated 200,000 children from South Korea have been sent overseas through inter-country adoption. Ninety percent of children sent abroad through inter-country adoption from South Korea in 2009 were children of unwed mothers. According to the U.S. Department of State, China sent an estimated 3,000 children to the United States in 2009.

Tentative Support

Supporters of the bill claim it will help address what they deem China’s lack of willingness to cooperate on issues pertaining to North Korean defectors, as well as a lack of resources to address related social welfare issues.

“Overall, I see positive intentions behind this law,” said Seok. “Orphanages are not ideal, and there is a lack of financial resources in those areas of China where children of North Korean mothers reside that are available in countries like the U.S.”

However, Seok notes that there are potential practical problems.

“If this law were to pass, first and foremost, the organizations that are a part of these measures would have to work with China, and it is not a given that China’s government will agree to cooperate,” said Seok, speaking of the bill’s challenges. “Second, they need to verify documentation about the children and their parents, which will be the most difficult task they will face.”

In addition to highlighting the lack of financial resources in China to address this issue, experts also consider China’s policies toward North Korean defectors.

“When China’s rigid or hostile attitude toward North Korean defectors is considered, inter-country adoption is one of the possible options to resolve this kind of dilemma,” said Kim Jong-chul.

Criticisms

Inter-country adoption remains controversial in circles of academia, social welfare, and human rights. In addition, the Hague Convention mandates that the first priority is in keeping families together, looking to domestic adoption as a second alternative, and inter-country adoption as a last resort.

The inter-country adoption program that launched in South Korea in the aftermath of the Korean War was the first of its kind.

“As previously hidden histories of American adoption of that generation have surfaced, they - as with subsequent generations of adoptees - were often doubly traumatized by the very humanitarian process meant to liberate them from poverty and suffering,” said Christine Hong, professor of Critical Pacific Rim Studies and Korean Diaspora Studies at UC Santa Cruz in the United States in regards to the inter-country adoption program.

“Who has the authority to determine if these children have indeed been socially orphaned and surrendered for adoption?” asked Hong. “This resolution does not begin to address these fundamental questions that any ethical overseas adoption program must address.”

Others have pointed to the need to address root causes of the issue.

“Public policies have to include a way to overcome this emergency situation and a means to normalize or legalize the family situation of Chinese men and North Korean refugee women,” said Reverend Kim Do Hyun of Koroot, a group that provides support for inter-country adoptees from South Korea.

Alternative Legal Avenues

The legal complexity woven around the children of North Korean mothers in China remains a stark reality. Indeed, the issue has permeated into legal systems in China, South Korea, North Korea, a number of countries in Southeast Asia in which defectors reside, and the United States, among others.

In its report, Human Rights Watch recommends not inter-country adoption, but that the Chinese government “allow hukou registration for all children with one Chinese parent without requiring verification of the identity of the other parent,” among its suggestions.

“The problem is not the absence of a law in China,” said Kay Seok, who is also a supporter of the bill. “The issue is the enforcement of the law, which should take place without penalizing the children’s parents.”

In addition, Kim Jong-chul, also a bill supporter, said in regards to the will to first seek to obtain hukou, “In reality, Chinese fathers are very reluctant to register their children because the one-child policy and their North Korean wife’s illegal status are obstacles.”

The Protection and Settlement for North Korean Defectors Act passed by South Korea’s National Assembly 2007 is the legal mechanism through which North Koreans who have left the country may gain lawful recognition as South Korean nationals. It is based on a South Korean constitutional provision that defines the Republic of Korea as the entire Korean peninsula, meaning that people from North Korea are eligible for lawful recognition in South Korea.

The language of the North Korean Defectors Act implies that only those who previously held North Korean citizenship are eligible. Legal experts say that a clarification upon or amendment to the law’s definition of North Korean defectors could grant children, along with their mothers, recognition as South Korean nationals. This may effectively be an alternative solution to the de facto statelessness of the children.

The language of H.R. 4986 also makes it unclear as to which children fall within the scope of the programs that may be created under the bill. The bill states that the children that will benefit from inter-country adoption are orphaned North Korean children who do not have families or permanent residence, as well as orphans with Chinese fathers and North Korean mothers living in China and any eligible North Korean children. Such language leaves ambiguity as to which children the bill refers to, and therefore, which children may be determined “eligible” for inter-country adoption through a newly-created documentation process.

“We would never take a child who we know has a parent that is still alive and pretty much put them through this process for adoption,” said LiNK’s President Song, who later added that she also supports directly contacting parents to confirm relinquishment of children. The current language of the bill, however, does not clearly articulate those sentiments.

The bill has been referred to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs according to U.S. legislative procedure and is likely to go through a number of stages of discussion, markup and further amendments prior to being finalized and presented for a vote by the Congress.

By Kimberly Hyo-Jung Campbell

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/426317.html