Illegal foreign adoptions How Adoptees Demand Education

In the 1970s and 1980s, it was relatively easy for couples who were unable to have children to adopt a child from abroad. Today, these children are adults. When they search for their biological parents, they often find out that their adoption was illegal and that the documents were forged.

Isabel Fuhs wants to know who her mother is. "I keep asking myself that. But I imagine that she is somewhere." Isabel Fuhs was adopted from Brazil in 1985. She was not even two months old at the time, a small baby. But she knows almost nothing about her first weeks of life. Her biological mother was said to have been only twelve years old at the time of her birth. A Brazilian lawyer arranged the adoption in Germany.

"The story of my adoption is really very strange. There is nothing, no records, in which hospital was I born? There is also nothing about my biological parents, i.e. my mother, no name. It is really very unclear. You can't understand much anymore today."

It is a painful gap in their biography. Psychologists have long known how important knowledge of biological origins is for identity formation. In 1989, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that knowing one's own ancestry is one of a person's personal rights. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child also contains the right to identity. Not knowing anything about one's biological family plunges some adoptees into deep crises.

right to know one's own ancestry

For Isabel Fuhs, too, the day came when the question about her biological mother began to hurt. "It was actually my 18th birthday, when for some reason I got it into my head that my biological mother would contact me on that day. I always expected that to happen."

An expectation that was not fulfilled. Isabel Fuhs is like many people adopted from abroad who know little or nothing about their biological origins and who do not have any meaningful documents about the circumstances of the adoption. This is primarily a result of very lax controls on foreign adoptions up until the 1980s.

For a long time, in Germany - as in other western countries - it was relatively easy for couples with an unfulfilled desire to have children to bring a baby home from a developing country - much easier, for example, than applying for one of the few children available for adoption in this country. Many couples paid horrendous sums for the placement, and this gave rise to an industry with illegal practices: biological parents in the countries of origin were threatened or not properly informed about the consequences of adoption, and their children were extorted or bought from them.

Criminal lawyer: “Foreign adoptions were viewed relatively uncritically”

"Basically, I would say that an adoption, an international adoption, is illegal if a child who should not actually be in the adoption system has entered the system." Elvira Loibl is an assistant professor of criminal law and criminology at the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands. The Austrian researches child trafficking and illegal international adoptions. These are only possible through so-called child laundering:

"So, child laundering. After the child has been obtained illegally, the child is laundered, which means that the adoption papers, birth certificates, etc. are forged or fabricated to make the child look like a real orphan. So, you basically try to conceal the child's illegal origins."

According to Loibl's research, placement agencies and youth welfare offices in Germany have not actively participated in such illegal practices. However, they have probably stabilized the system - by turning a blind eye and not asking questions. For a long time, there was also little awareness that the adopted children are not always being done a favor.

Added to this was something that experts call the white savior complex: the desire of white couples to take black children out of poverty - a phenomenon that has been critically questioned in recent debates about colonialism. "At that time, people still believed that adoptions were basically a good thing, that they were helping, that they were saving children from poorer countries. So back then, people still viewed foreign adoptions relatively uncritically."

Debate about the role of the state flares up across Europe

The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs has declined an interview request on the subject of international adoptions. In response to a written request as to whether government agencies had ignored illegal practices in international adoptions in the past, a spokeswoman stated:

"In some European countries it has become clear that there were irregularities in the adoption of children from non-European countries in the 1970s and 1980s. As far as adoptions are concerned, there is currently no evidence that comparable irregularities occurred on a larger scale in Germany."

Criminologist Elvira Loibl sees it differently. As evidence, she cites a small but meaningful study by adoption expert Rolf Bach from 1988. It states: "In 70 of the 300 completed adoption files, clear indications of commercial, illegal or criminal practices were found. This means that 23 percent of all adoptions of children from the Third World or 42 percent of private adoptions contradict the current adoption regulations of the Federal Republic and - as a rule - also of the foreign countries of origin."

Problems with international adoptions were already known back then. The fact that the Ministry of Family Affairs is now comparing itself with other European countries and is apparently of the opinion that there is comparatively little to complain about in this country could also be due to the fact that there is already a heated political debate in other countries about the role of the state in international adoptions. Loibl from the University of Maastricht cites the Netherlands as an example:

"Here in the Netherlands, there were more and more adoptees who started searching for their roots, for their origins, and who realized that they were not actually given up by their biological mother, but that they were actually kidnapped, for example."

Successful claim for damages in the Netherlands

A Dutch woman who was illegally adopted from Sri Lanka as a baby has successfully sued the Dutch state for damages. The Dutch government also set up a commission of inquiry that uncovered abuses in the international adoption system. In 2021, international adoptions were even temporarily stopped altogether in the Netherlands as a result.

"So, I think the Netherlands is a really interesting case because there are so many adoptees who are really taking to the streets and demanding redress and also recognition of the harm that has been done to them."

Similar debates and investigations are taking place in Belgium, Switzerland and Sweden. In Germany, the issue has been relatively quiet so far. But that could change. One person who is fighting for it is adoption critic Melanie Kleintz. "For the simple reason that many adoptees here in Germany suffer because their adoption was not legal. I think it is part of our lives that we really acknowledge that and apologize for it."

Social worker: Foreign adoptees have a higher risk of suicide

Melanie Kleintz was adopted from Peru in 1980 - and she has collected a lot of evidence to show that her adoption was also illegal. Her biological mother died shortly after her birth, and her father was apparently pressured to give the child away. A Catholic children's home is said to have been involved, money was exchanged, and documents were doctored. "It later came out that I am actually a year younger, that I was not born in 1978, but in 1979. And I now have four birth certificates, all of which are false."

When she became a mother herself, all the pain came out, she says. That's when she started looking for her biological family in Peru. She found her father in the small village where he still lives. Today, she no longer has contact with her adoptive parents. Since then, Melanie Kleintz has made it her mission to represent the interests of foreign adoptees in Germany. The social worker is involved with InterCountry Adoptee Voices, an international organization for foreign adoptees. She advises people who are searching for their origins on the other side of the world and are stuck when documents are missing or forged.

She receives hundreds of inquiries every year. Many people who contacted her suffer from depression. There is evidence that people adopted from abroad have a higher risk of suicide. However, there are no reliable statistics or studies on this. Melanie Kleintz is calling for an independent commission of inquiry to find out how many illegal adoptions there were in Germany - and who could have prevented them. She would also like to see a public apology. She is also calling for more state support if people who have adopted want to search for their roots. "We adoptees need something that can be explained - how did it all happen?"

Adoption laws have been tightened

A state commission of inquiry - and a public apology? The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs has no plans for this, "there are currently no considerations about it," explains a spokeswoman. Melanie Kleintz is disappointed: "We had no lobby. We still don't have a lobby. On the contrary. The Ministry for Family Affairs actually only ever supports the wishes of the adoptive parents."

However, she admits that adoption laws have been tightened significantly. The most important is probably the Hague Adoption Convention, which Germany ratified in 2002 and which provides strict rules for international adoptions, such as counseling and consent from the biological parents and a suitability test for adoption applicants. The Adoption Assistance Act, which has been in force in Germany since 2021, provides for further protection standards.

Privately organized international adoptions have been prohibited since then; anyone who wants to adopt a child from abroad must generally either contact the adoption offices of the state youth welfare offices or one of the state-recognized independent organizations. These include the "Help a child" association from Rhineland-Palatinate, founded in 2004 by Bea Garnier-Merz: "To date, we have placed around 800 children from Haiti, Burkina Faso, Mali, Kenya and the Dominican Republic."

She and her husband have adopted a son and a daughter from Haiti in addition to their three biological children. Because the first adoption didn't go well, she came up with the idea of setting up her own adoption agency. She does this on a voluntary basis; she works in the German army's social services. But of course her organization also employs specialists who oversee adoptions, prepare applicants and arrange travel. A placement costs just under 10,000 euros, plus travel costs and various fees in the country of origin and in Germany.

Stricter documentation leads to overcrowded homes

The new laws have made adoption much more difficult and time-consuming, says Bea Garnier-Merz. "In the past, it was a matter of two years at most! And today you can expect three to five years. It has become more difficult. Haiti, for example, always says that we would like to return to the way things were before. The homes are full to bursting." Garnier-Merz reports on the poor conditions there, on mothers who have many children and cannot feed them. The fact that adoptions take so long these days is not only perceived as a burden by the applicants. It is also a disadvantage for the children.

"After a certain age, adoption is no longer an issue. No one comes around the corner and says, I would like to adopt a child aged eight or ten. We experience this in Haiti when we are in children's homes and there are older children who have been there for a long time, they come and say: Is there no mother for me?"

Garnier-Merz also knows the stories from the 1980s about the criminal trade in babies from all over the world. She herself has had other experiences, and tells of desperate mothers in Haiti who wished their children a better life elsewhere without hunger and poverty. Every adoption is meticulously documented, her association submits annual reports and is in contact with the state youth welfare office. Adoption critic Melanie Kleintz also believes that international adoptions can generally be successful and, under certain conditions, are a stroke of luck for the children:

"There are unwanted children all over the world and they need a safe place and there are adoptive families who can offer that. So I can't say that I am against adoption and that adoptions should be banned in principle."

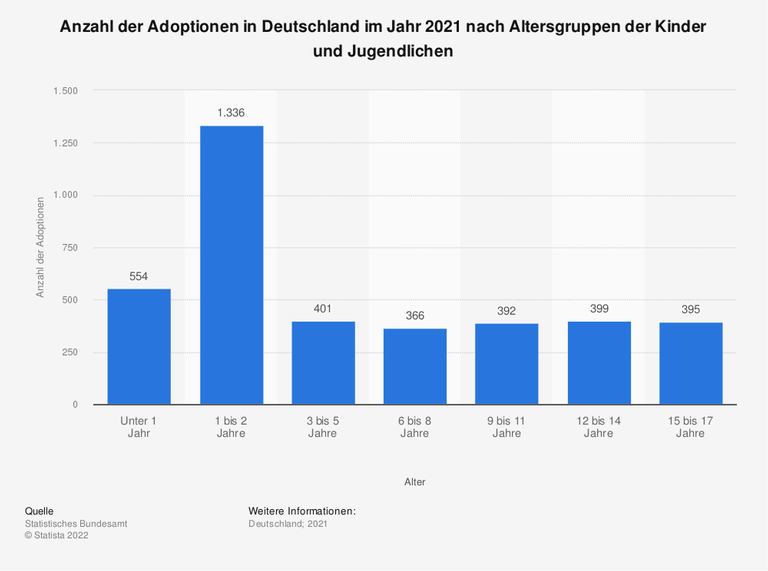

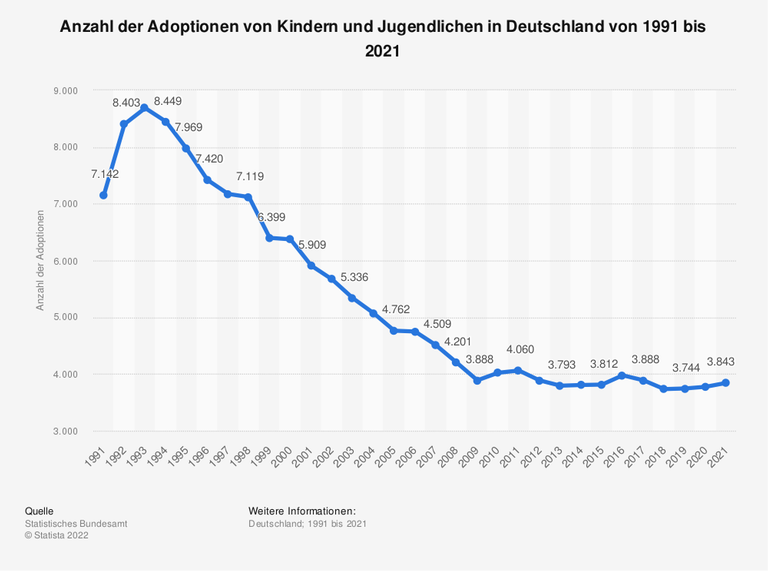

Adoptions are declining sharply overall

However, both domestic and international adoptions are declining sharply in Germany. This is probably mainly due to the success of reproductive medicine: more and more couples with unfulfilled desire to have children can be helped with artificial insemination. International adoptions are becoming increasingly rare: in 2021 there were only 111 compared to almost 1,000 in 1992. "I also regret that many children no longer have a chance because of this," says Bea Garnier-Merz.

(Statista)

When a child is placed in an adoptive family, the files on it must be kept for 100 years in Germany. And at the age of 16, the adopted child has the right to inspect the files. "We now have adult adopted children. Many of them contact us at some point and ask, can I look at my files?"

Her association then accompanies the adoptees in this research, provides them with trauma experts and gives them the opportunity to talk. Bea Garnier-Merz also offers so-called root trips to get to know the biological family in the country of origin. Sometimes the adoptees are disappointed - but it is still an important experience. "Everyone has the right to know where they come from. And to want to see their parents, if they are still alive. I think that is absolutely important for one's own identity."

Everyday racism because of dark skin and dark hair

An accompanied and organized journey back to her roots to her biological family – that is something Isabel Fuhs, who was adopted from Brazil as a baby, can only dream of. She too had started looking for her mother. She commissioned a Brazilian woman to visit hospitals and children's homes in the area, to collect every possible lead – in the hope of finding some clue about her mother.

"I always thought that there was something for me in Brazil, a piece of family, a piece of me. And in order to make this story a reality, it was really important for me to look for it." Her adoptive parents always supported her. Her relationship with them was warm and intact. "I always find it difficult to use the word 'adoptive parents' because that doesn't exist for me. They are my parents. And it has always been that way."

Nevertheless, she struggled with her identity for a long time. Added to this were experiences with everyday racism, xenophobia, and constant questions about where she came from with her dark skin and dark hair. "I'm always different somehow. For me that means: I don't belong here, I don't belong there. And who am I anyway?"

Could her biological mother give her an answer? She doesn't know. The search was unsuccessful. When Isabel Fuhs was told by a Brazilian children's home that she shouldn't dig any further, she stopped. Perhaps to protect herself from disturbing information. "I think that a lot of things went wrong, possibly even some illegal things. But also questions that I don't want to ask myself because I don't want to hear the answers."

That doesn't mean that she's finished with the issue - but other things are more important at the moment, her own family - she is the mother of a son. "I have my family, a person who looks like me, a biological relative, that I created. So I started the path forward and not backwards. And that really helped a lot in saying that I can't go any further at this point. But that isn't a final decision for ever."

Because maybe one day she will start searching again, travel to Brazil and search for her biological family there.