Crucial data on hundreds, and possibly more than a thousand, children adopted in the Netherlands has been destroyed. Starting in 1970, their personal records, which contained information about their biological parents, were erased.

It starts with a relatively innocent question. Three years ago, a cousin of Liesbeth Struijcken (56) asked on Facebook whether their last name is now spelled with an 'ij' or a 'y'. What difference does it make, she thinks. But she still decides to dive into the trunk in the basement containing all her adoption papers. Surely the correct spelling of their last name is in there, she reasons.

Once in her basement, she feels dizzy as she realizes she'd never really looked at the pile of papers before her. Struijcken is adopted; she discovered this by accident at age nine, during a vaccination at school and a name she hadn't known was read aloud. It turned out that the name she hadn't known was hers.

For the first time, she now sees two documents in the basement that she had always overlooked: one in which the Breda Child Protection Council informs her parents that they can have their adopted daughter's personal record rewritten, omitting all information relating to her adoption. The second letter confirms that her information has indeed been destroyed, with the authorization of the Minister of the Interior.

Struijcken is stunned. “I felt utterly betrayed. That identity card is much more than a simple card. It symbolizes that entire adoption history. Your identity card tells you who you are. That's true. Not for me.” Until 1994, the Dutch government kept information about its residents on identity cards; now all that data is stored in the Personal Records Database.

Personal identity cards of adopted children were permitted to be destroyed after a 1970 ruling by the Council of State. At the request of adoptive parents, the Council ruled that adopted children were entitled to a new personal identity card, on which their biological parents were no longer listed.

Surrogate mothers and foster children

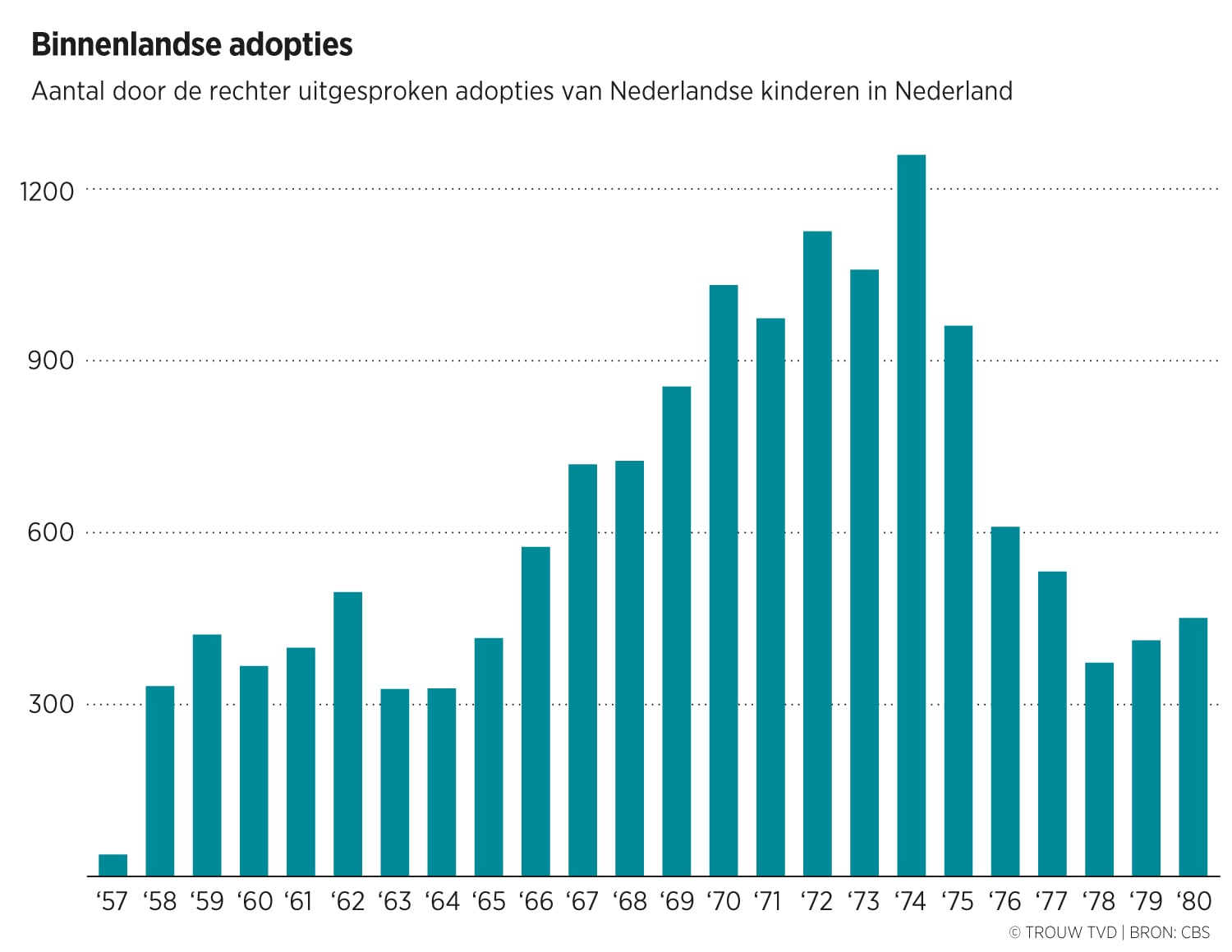

The adoption law seems to have created its own dynamic in the Netherlands, according to research by Trouw and Omroep Gelderland. One in which unmarried women were pressured to give up their babies or even, decades later, claim to have been forced to give them up. Estimates of the number of women who gave up their children between 1956—when the adoption law came into effect—and 1984—when abortion was legalized—range from 13,000 to 20,000. This is despite the fact that Fiom (Federation of Institutions for Unmarried Mother Care) mediated for 328 children who had been relinquished in the preceding twenty years.

In a series of articles, available at trouw.nl/adoptie , we investigate what went wrong, how it could have gone so wrong, and the impact it has had on people's lives. The interviews and videos from Omroep Gelderland can be viewed here. Also listen to the special podcast.

In the late 1960s, the Ministry of the Interior received the first requests from adoptive parents who wanted their child's "illegal" start removed from the population register. Adoptive parents believed this would be in the child's best interest. The Minister was authorized to transfer identity cards "in exceptional cases" without transferring all the data to a new card, and the adoptive parents believed the Minister should do so in this case.

Initially, however, the National Inspectorate of Population Registers refused. Several couples responded that a complete population registry is more important than the child's best interests. Moreover, for genetic and ancestry research, it would be undesirable for an adopted child to appear as if it were the biological child of its parents.

The Central Adoption Council, which advises the Minister of Justice on adoption, among other things, disagrees. In 1965, it recommended adjusting children's identity cards "to reflect the changed circumstances."

Since the Adoption Act of 1956, the number of approved adoptions has increased significantly.Source Thijs Van Dalen

A persistent couple

That this ultimately happened was entirely due to a persistent couple from Alkmaar. In November 1968, they submitted a request to then-Minister Hendrik Beernink to transfer the identity card of their recently adopted son Jacobus "with the omission of all information that could indicate his illegitimate origin." The couple feared that otherwise, the then four-year-old boy would suffer the consequences for the rest of his life. Women who had given up a baby were already allowed to apply for a new identity card at that time, one that did not include their biological child.

The National Archives shows what the boy's identity card looked like at that time: the first names his biological mother must have given him, his last name, and his biological mother's full name are crossed out, but still legible. His new first names and last name are also on the card, as is the maiden name of the woman who adopted him.

When the ministry refused to amend their son's personal identity card, the couple appealed to the Council of State. The national inspectorate again wrote that there was no reason to destroy the original data on personal identity cards: not everyone had access, municipal officials were required to keep information confidential, and it was inconvenient for a new personal identity card to appear as if a child had been born to the adoptive mother. "I don't know why you would do this," the head of the national inspectorate wrote to the Minister of the Interior in September 1969.

Accountability

For these stories, Trouw and Omroep Gelderland conducted archival research at Fiom, the national inspectorate of population registers, and the Gelderland Archives, speaking with mothers, children, other stakeholders, experts, and researchers. Previous research and explorations into relinquishment and adoption were also consulted. Sylvana van den Braak searched the Fiom archives. Information about the Central Adoption Council was obtained thanks to Eugenie Smits-van Waesberghe.

But what no one seems to have expected happens anyway: despite another couple being denied a year earlier, this couple from Alkmaar was vindicated by the Council of State. In February 1970, the Council ruled that personal records may be copied, and that all biological data need not be included. The old records are sent to the national inspectorate for destruction.

This ruling differs from the previous one because the couple from Alkmaar is making a concession: the new identity card will indicate that the child's name was changed after adoption. The idea is that this will make it clear that the child was not born to the mother listed on the card, and that children, once adults, can always request their birth certificates when searching for their biological parents.

The ruling prompted more adoptive parents to request a new identity card for their child. They applied for one to the Ministry of the Interior, which then delegated the processing to the National Inspectorate of Population Registers. In the following years, the requirement that a child's adoption be clearly stated on an identity card was quickly abandoned. In February 1975, the head of the National Inspectorate of Population Registers wrote to the director of Child Protection Services in Breda that "for some time now, the requirement that the adoption be stated on the new card has been waived." This practice violated the Council of State's ruling, but was legally permitted.

Struijcken's card, which was created after her adoption in 1973, no longer shows that her adoptive parents are not her biological parents. There's also no reference to adoption. "Who can answer the question of why that information had to be destroyed?" she asks. "And what was so urgent about this that the Minister of the Interior had to issue a ruling?" Officially, each request had to be considered by the Minister, because the law didn't stipulate that adoptive parents have the right to a new identity card for their child.

Her parents can no longer answer the question of why her information had to be destroyed. They are both deceased. Her adoption history is also complex: the name Struijcken comes from the man she calls "father number two," her biological father is number one. Struijcken's father died when she was three, and the adoption was granted posthumously when she was ten. Before that, her mother remarried "father number three," with whom Struijcken had a close relationship. She dedicated the book she wrote about her life to him. "Because through all my searching, I was allowed to be your daughter," she wrote.

The letter from Child Protection Services to Struijcken's parents was accompanied by a standard form with a request to the minister. These forms were created because, following the Council of State's ruling, many parents are sending letters requesting a new personal identification card for their child.

An example of such a model application can be seen in a letter sent by the National Inspectorate to the municipality of Hennaarderadeel in 1974, with the intention that the municipality could send it back to parents after the adoption had been granted. Parents only had to enter their own information and their child's date of birth. This was followed by a request to copy the personal record, omitting any information "that could in any way indicate the adoption had taken place."

The idea that children's birth certificates could always answer the question of their biological ties has proven untenable half a century later. For example, adoptees don't know where they were born or registered. Birth certificates must be requested in the place of birth. So, if you don't know where you were born, you can't request a certificate. While adoptive parents were supposed to inform their children about their life history, not all of them did.

Omroep Gelderland produced the item below, in which Emmy van Schalkwijk explains how she spent years piecing together the puzzle of her identity.

This also applies to Struijcken's parents. "You have to remember that for a long time I thought I was born in Tilburg, because that's where I lived," says Struijcken. "While I was born in Breda." Moreover, it takes a little while to even think of requesting that certificate, she says. "There's no guidance; you have to figure everything out yourself. I never even thought about requesting my birth certificate." Struijcken did so at the request of Trouw and Omroep Gelderland . New information has been added to her birth certificate in the margin, but the biological information has been retained.

History repeats itself

The right of children to know their origins is a fundamental right, Struijcken emphasizes. "The wishes of those who want a child should not be more important than the rights of that child." In adoptions, it often comes down to what the intended parents want, says Struijcken. "The decision has been made for us."

She also fears history is repeating itself. "I'm not angry or anything, but discussions about egg donation and surrogacy really get to me. If an egg comes from Sweden, or a surrogate from the US, how is the right of children to know where they come from guaranteed?"

Response from the Ministry of the Interior

In the current system, parents have the option to have pre-adoption data removed from the Personal Records Database (BRP) for the sake of the child's privacy. This option exists because this data is personally sensitive and not necessary for the performance of government tasks. However, removing this data from the BRP/population register does not affect the source documents such as civil status records (including birth certificates) and the underlying documents (such as the court ruling on the adoption). In the best interest of the adopted child, the original data must be available at the municipality. As the BRP is further developed, it will be determined whether adjustments to the current system are necessary in this regard.

The specific case you describe requires further investigation, partly because it goes back a long way. In general, even during that period, it was already possible to have pre-adoption data removed from the Personal Records Database (which at the time consisted of paper personal records, now on digital personal records)